A mutational atlas for Parkin proteostasis

This is my attempt to summarize this article by Clausen et. al, by rewriting it in more “normal” language. See my Paper Reading for more.

The short version

- The article uses a high-throughput scanning method (VAMP-seq) to quantify the abundance of 9219 out of 9300 possible Parkin variants in cultured human cells.

- Most low-abundance Parkin variants are proteasome targets, found within the structured domains of the protein. When these occur the protein misfolds and is targeted.

- The authors find strong evidence for a degron region located next to the activation element in Parkin.

- Half of known disease-linked Parkin variants were found to have low abundance.

The questions I’m left with after reading this article?

- The authors propose that:

most of the low abundance Parkin variants are likely subject to PQC-linked degradation due to an underlying destabilization of the native fold

- or in simpler terms, the variants with low abundance are so because the mutated structure is less stable and therefore they’re red-carded and destroyed

- how can we probe whether this is actually true? My first thoughts are to analyze these with a smFRET-assay or a similar structural probing assay, but this would depend on the dynamics of the protein itself.

- It’s possible that the low abundance of the most C-terminal Parkin tile is due to Parkin carrying a C-degron.

- The authors offer up the supporting case that clipping the last residue/amino acid increases abundance.

- How would we find out whether this is the case? Could we inhibit all other degrons, and then change the C-terminal to find out whether it contributes degron activity?

The Parkin Protein

The Parkin protein plays a central role in marking proteins for degradation, or destruction, and is therefore an essential part of the Protein Quality Control system in cells. Specifically, the Parkin protein labels proteins in damaged mitochondria, and as such acts as a “mitochondria bouncer” regulating whether damaged mitochondria should be broken down and recycled, a process known as mitophagy. When a Parkin protein encounters a protein queued for removal (a “target”), it binds a ubiquitin protein to the protein, kind of like giving it a “red card”. This ubiquitin “red card” alerts the proteasome, or the “protein trash compactor” that the protein should be degraded and recycled. In this way, the Parkin protein is vital component for cells to maintain proteostasis, or the balance of proteins within the cell.

Mutations in the Parkin protein are linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, as damaged mitochondria are not removed from cells when the Parkin protein doesn’t function properly. In turn, these mutations are associated with the neurodegenerative disorder known as Parkinsons’ disease and cancer tumor formation. It’s therefore important to understand what effects different mutations have on the Parkin protein’s structure, activity, and stability. In the long run, mapping these mutations in the Parkin protein can help understand, predict, and treat diseases related to Parkin.

Structure of Parkin

The Parkin protein is composed of a single chain of 465 amino acids, divided into 7 domains/sections of amino acids:

- A Ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain, which keeps the Parkin protein from red-carding itself.

- A disordered part containing the “activation element” (ACT)

- A Really Interesting New Gene domain (RING0)

- A RING-between-RING (RBR module), containing the “active site”, composed of

- Another RING domain (RING1)

- An In-Between-RING domain (IBR)

- A repressor element (REP)

- Finally, the second RING domain (RING2) which contains the Cysteine (pos. 431) responsible for catalysis (the attachment of the “red-card”).

Protein Mutations

There are three types of naturally occuring protein mutations.

To understand them, it helps to understand the different levels of protein structure, which is wonderfully explained with this picture from Introductory Biology:

- Frameshift mutations introduce or delete a base pair in the DNA sequence. Because DNA sequences are read in sets of 3 at a time, a frameshift mutation typically will change the entire expression of the protein.

- Nonsense mutation change a single base pair to introduce a stop codon, effectively cutting off the tail of the protein.

- Missense mutations change a single base pair, which propagates to a single amino acid changing in the protein. These are the mutations that are studied in this article, since the two others typically “break” the protein outright.

Experiments

The authors used a technique known as “deep mutational scanning” to investigate every single substutution mutation in the Parkin protein. That is to say, for all 465 amino acids in the chain, there are 20 possible substitutions, since there are 21 essential amino acids. Out of these 465*20 = 9300 mutation candidates they manage to probe 9219 (99.1%) of the possible mutations, to create an overview over which regions are the most sensitive to mutations.

The way the authors compared the mutated proteins was by measuring relative abundances of the mutated Parkin protein, as a heuristic for stability and likelihood of degradation. If a given mutation has low abundance, that means one of two things:

- The mutated protein is for some reason difficult to produce in the cell, so the protein breaks down. before it has formed.

- The mutated protein is unstable and immediately red-carded and destroyed by the proteasome.

As an extra check, the authors include the pLDDT score of , which is AlphaFold (a Machine Learning model)’s computational prediction of stability.

Results

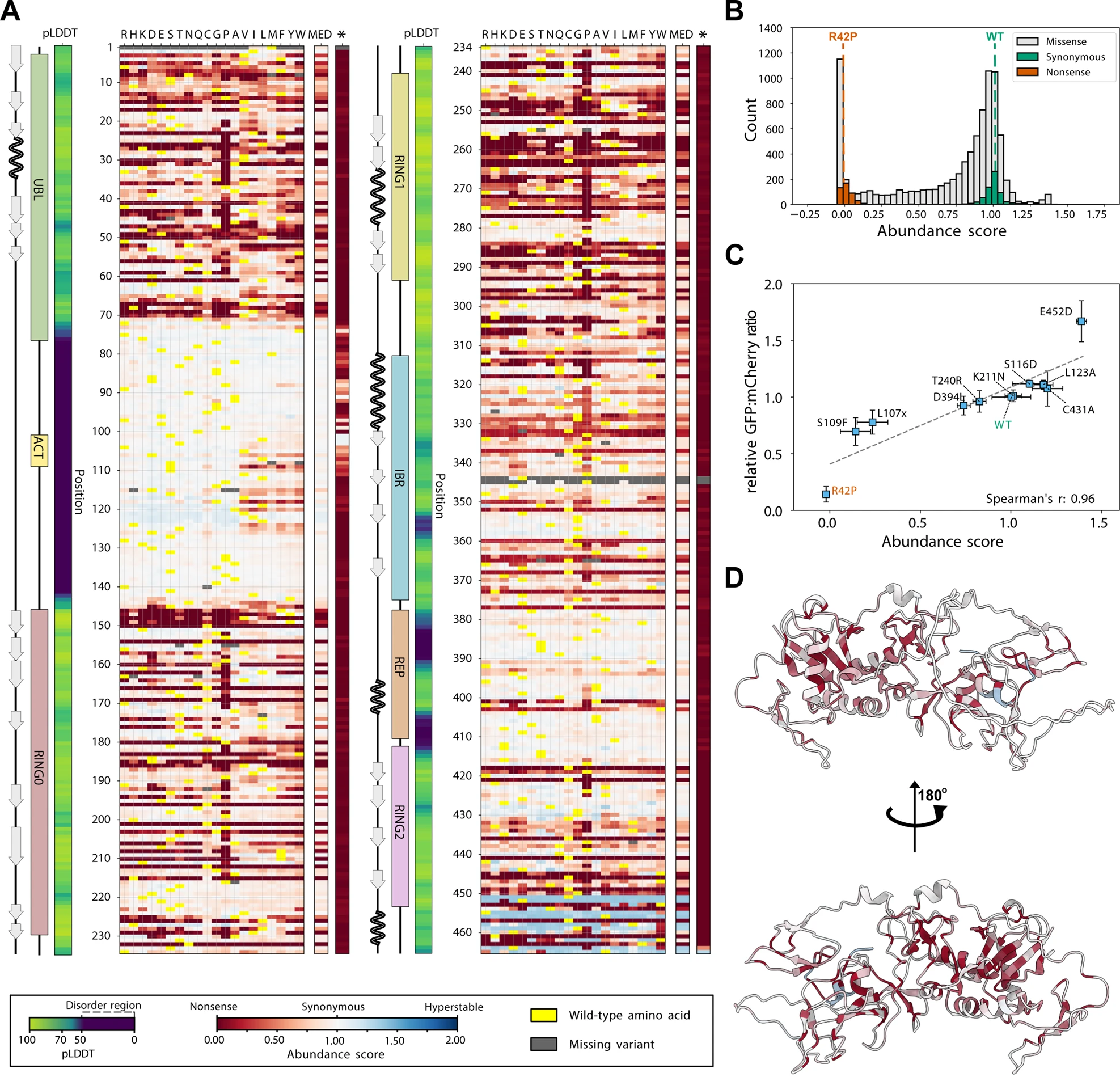

Effects of mutations on the Parkin protein abundance - Fig.2

This plot has a lot of data to unpack, which is in fact very exciting.

Fig 2.A shows a head map of the different mutations, where the vertical axis is the amino acid number and the horizontal is the code for the amino acid, with the corresponding abundance score for each mutation given by the color of the square.

On the left we see the different domains as mentioned above, as well as the pLDDT column which is a column from AlphaFold’s prediction of stability.

Yellow cells are the Wild Type (i.e. the not-mutated protein) protein.

In this chart, some cool effects pop out at first glance:

- the pLDDT score corresponds well to regions with little red, i.e. regions that are disordered are less sensitive to mutations.

- Proline substitutions generally have a strong negative effect on the abundance. This makes intuitive sense since proline is one of the most rigid amino acids due to its chemical structure.

- There seems to be very few “blue” areas, i.e. mutations that cause a higher stability than the wild-type protein. This suggests that the wild-type is one of the most stable variants of the Parkin protein.

- Fig 2.B also shows a histogram of all these numbers, and suggest that only a small proportion has abundance scores larger than 1.25.

- There is a grey area around AA 345. This is interesting since it’s so close to the active site C341.

Small note: Fig 2.D shows the predicted Parkin structure colored by the median abundance score, which basically shows us which regions are the most sensitive to a mutation. I really like this plot.

Low abundance Parkin variants are thermolabile proteasome targets

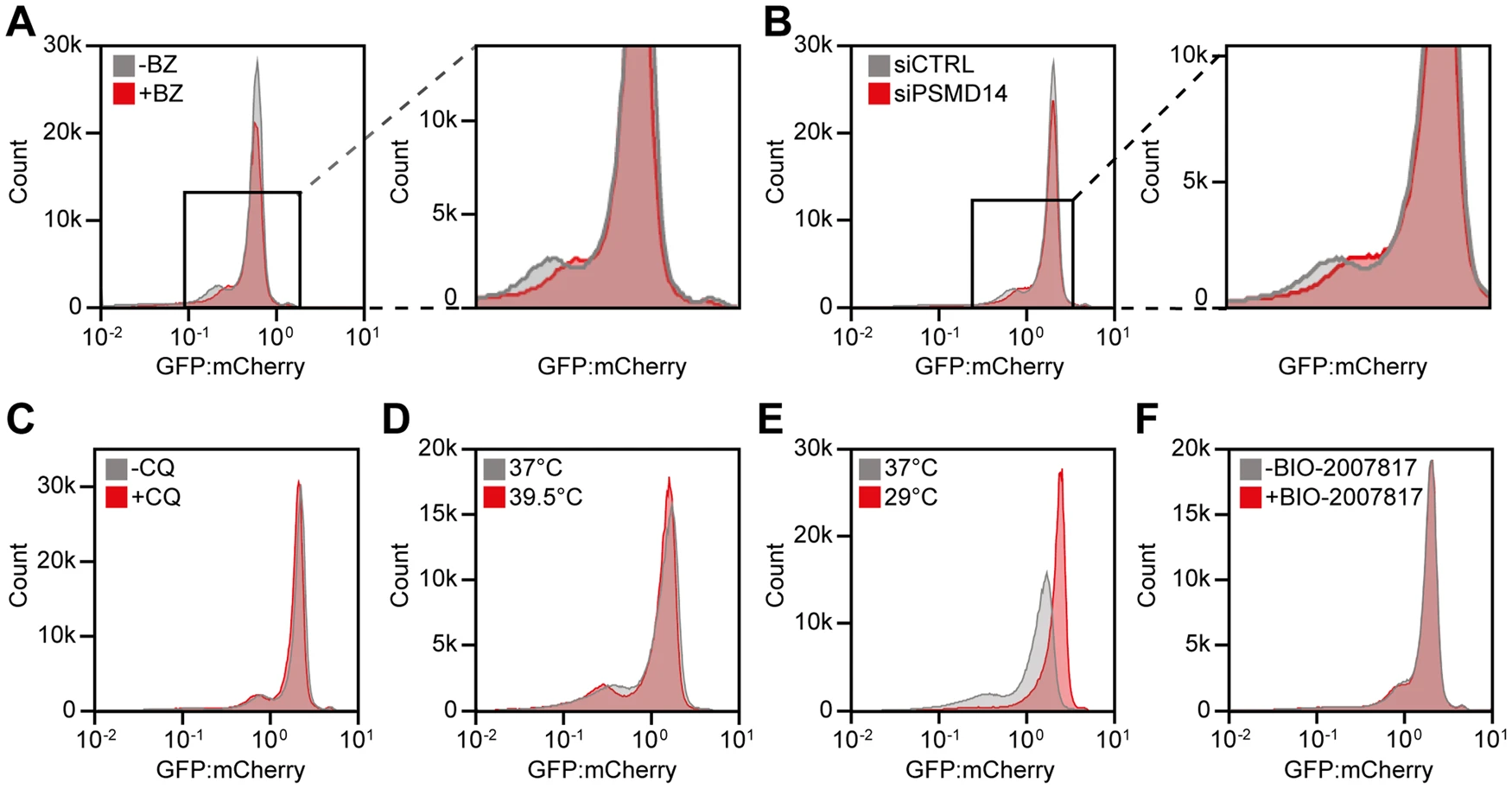

This figure is a bit less intuitive to interpret, but nonetheless interesting.

The experiment here involved treating cells modified to produce the PRKN variants as above, with two different drugs.

This figure is a bit less intuitive to interpret, but nonetheless interesting.

The experiment here involved treating cells modified to produce the PRKN variants as above, with two different drugs.

- Fig. 3A shows the abundance distribution after treatment with Bortezomib, which stops the proteasome (the protein trash compactor) from working. In this figure we observe that the peak corresponding to low abundance variants shift to higher abundance when the proteasome stops working.

- Fig. 3B shows the abundance distribution where a part of the proteasome has been knocked out, leaving the proteasome dysfunctional. Here the graph looks very similar to 3A.

- Fig. 3C shows the abundance distribution after treatment with Chloroquine, which stops the breakdown of internal cell components, a process known as autophagy. In this case we don’t see a large change.

In summary, these three results suggest that the proteasome is the pathway that degrades most of these low-abundance variants, i.e. they get red-carded and led to the trash compactor, not that they break down by themselves.

Inherent degrons overlap with mutation-sensitive regions

The authors then investigated degrons, or sections of the protein responsible for signalling that the protein is ready for degrading. They split the Parkin protein into 38 “tiles” or sections of amino acids and expressed independently, and used these to calculate a stability index across the whole protein sequence. Using a computational method known as QCDPred, the authors found that the more abundant tiles overlapped with regions that were more likely to be degrons. Comparing this to the weighted contact number (a number for how exposed a part of the protein is), the authors conclude that the degrons are, for the most part, “folded away” inside the structure. This is interesting, since we still don’t quite understand the structure and function of Parkin proteins when they’re activated.

Variant abundance correlates with stability and conservation

For investigating the link between abundance, stability and conservation, the authors calculate the theoretical folding stability of different mutants of Parkin and compare those to the cellular abundance scores. They find the following:

- Most of the low-abundance variants have low stabilities, suggesting that they can’t fold properly, and are therefore red-carded.

- Some variants have low abundance but high stabilities. These variants all have mutations on the parts of the protein that point outwards, which means they probably form a degron, which means they’re quickly red-carded.

- Out of these variants, some are known to be pathogenic, i.e. have been documented to cause disease in humans.

- This suggests that disease causing variants are so due to a loss in function, not structure of the protein.